Masked Gods Of The African Diaspora

The masquerade lives on: Interview with the American photographer Phyllis Galembo

7 Dec 2012

Interview and text by Sophie Pinchetti

All works courtesy of Phyllis Galembo

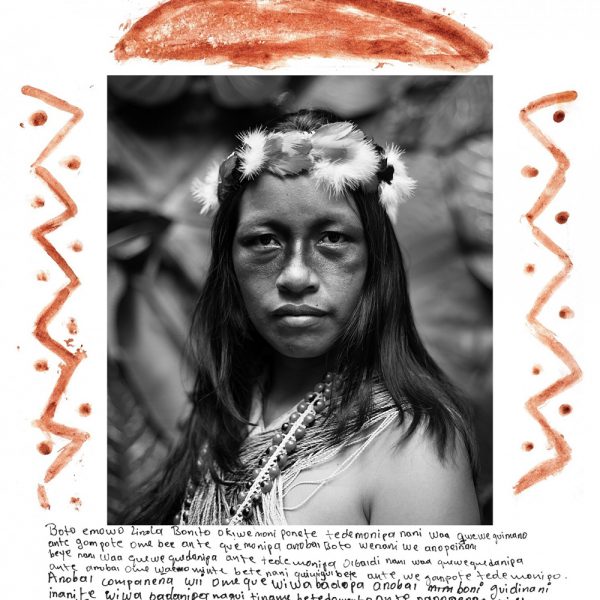

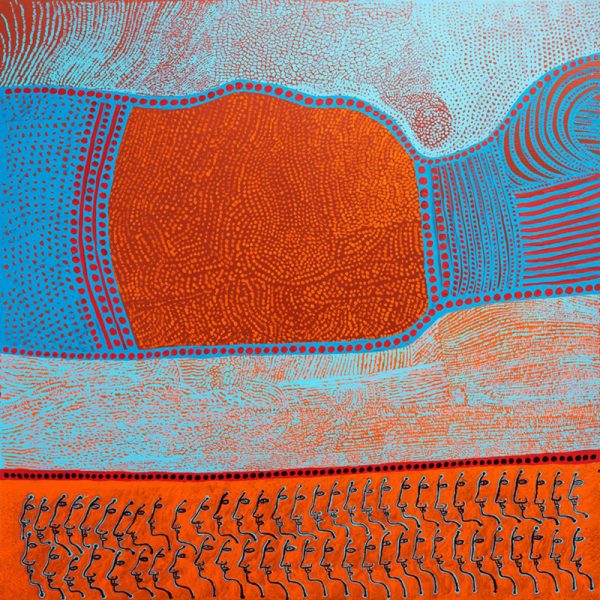

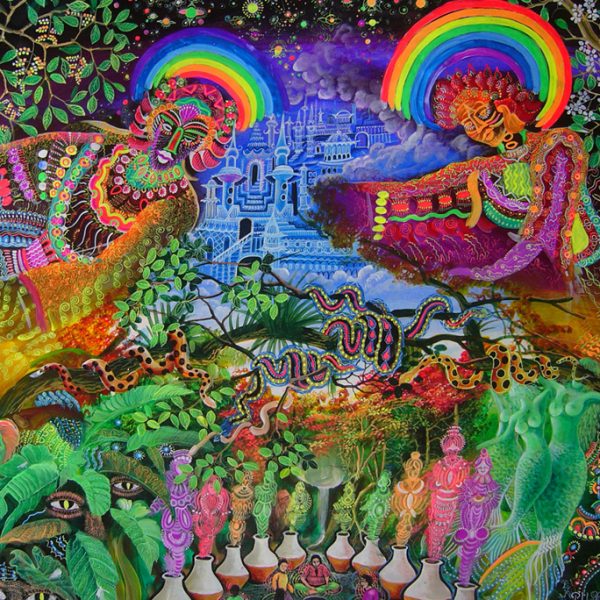

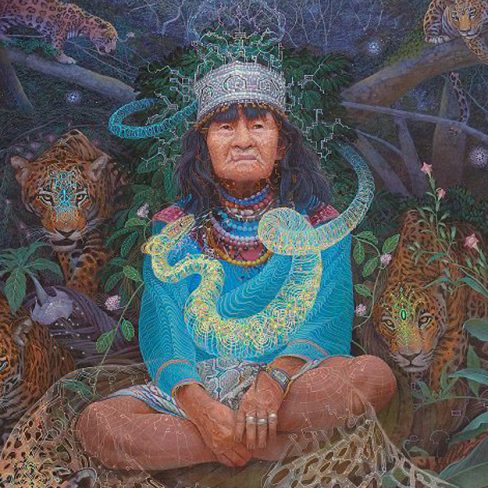

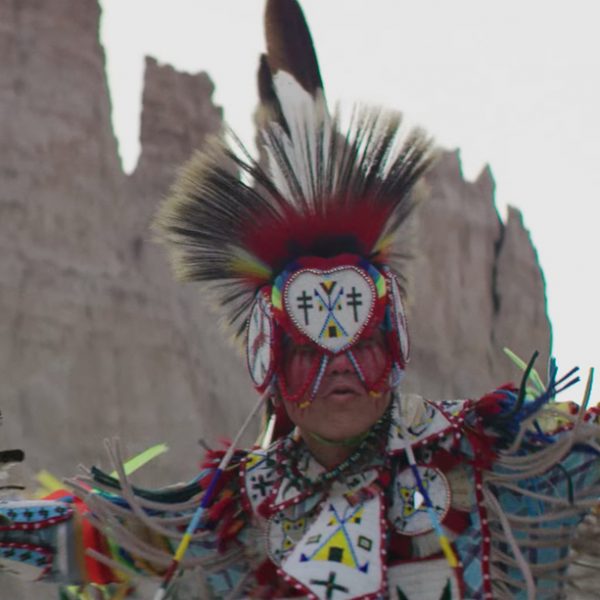

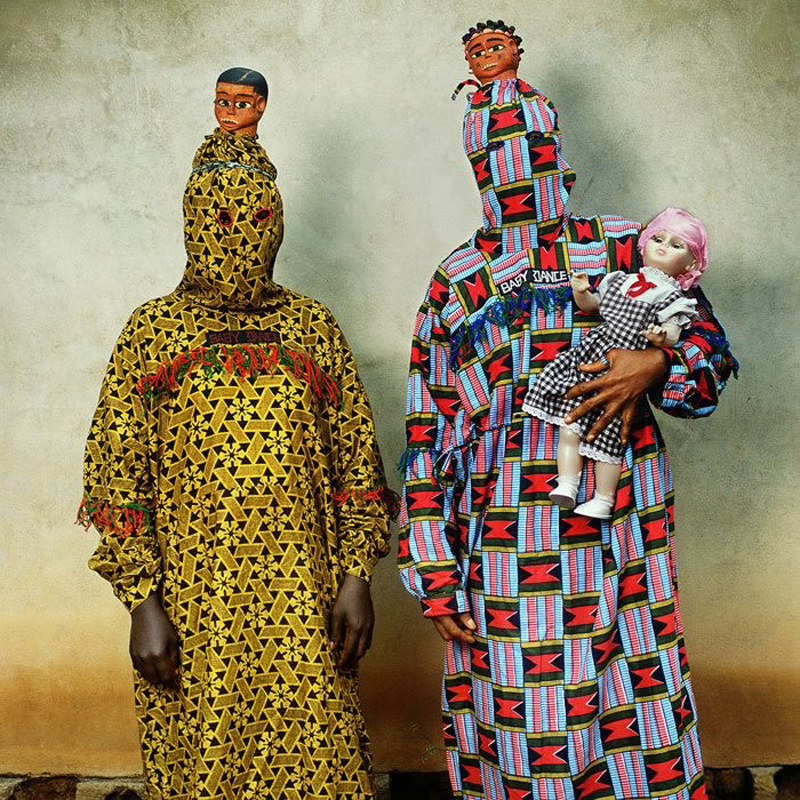

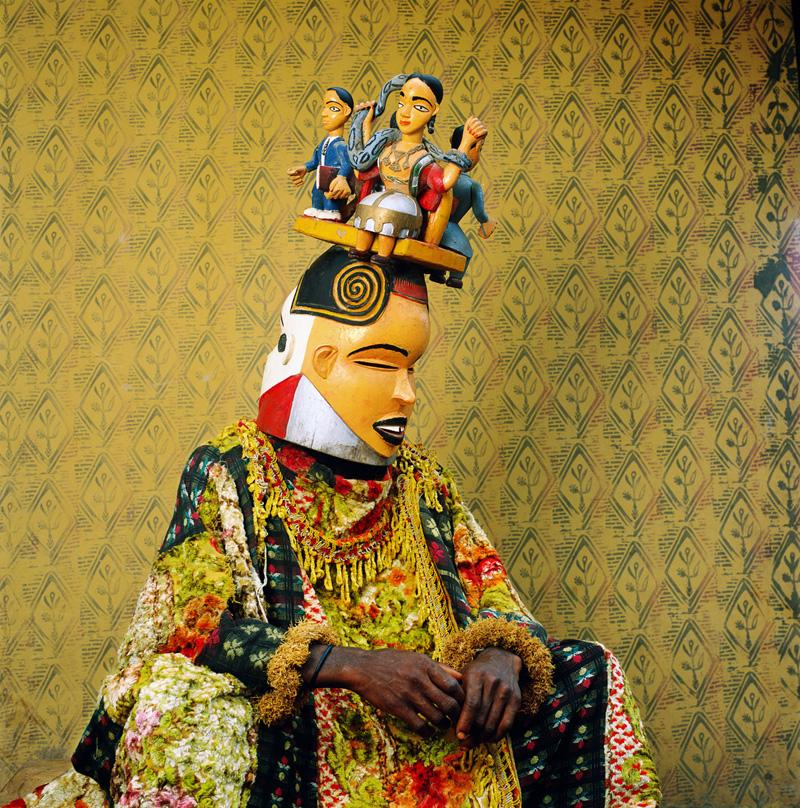

‘When the anthropologists arrive, the gods depart’, so goes the Haitian proverb. And what of the artist? Since the mid Eighties, American artist Phyllis Galembo has been documenting the otherworldly and fantastical manifestations of different faiths from around the world. At the crossroads between art and anthropology, Galembo’s lens has captured man’s tireless and universal desire to transcend the mundane. From Africa and the Caribbean, to Mexico, Cuba and even the USA, Galembo has photographed the global phenomenon of masquerade for nearly three decades. Interested in the physical – and often spiritual – transformation that takes shape through masquerade rituals, Galembo’s photographs pay testament to the integrity of this living and total art form. “I’m interested in the art people make, and how that is away in which people really express themselves”, says Galembo. Chronicling the physical creations, costumery and rituals of religious practice, Galembo’s portraits introduce us to a myriad of different spiritual leaders and healers, dramatic spirits, deities and forces.

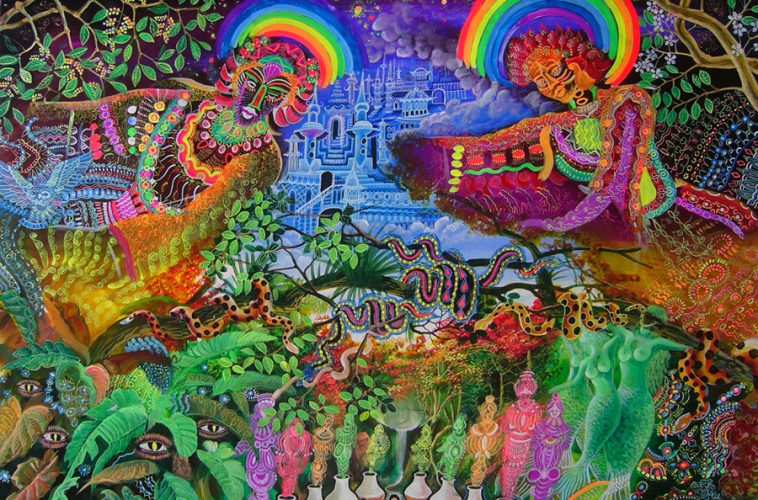

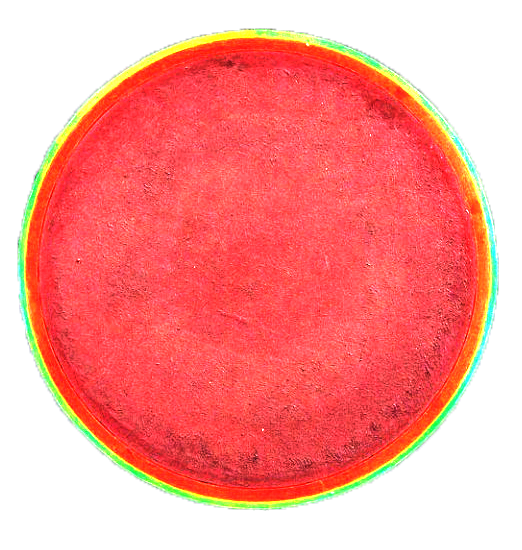

With a long-standing passion in African art, Galembo arrived in Nigeria in 1985. “I’ve always liked travelling since I was young”, she says, “and that started the whole thing. Through a friend I got connected and I ended up teaching in a summer program in West Africa on the Ivory Coast. I then went from Nigeria to Brazil and that’s when I did my work on Candomblé, which connects to traditional rituals that take place in Nigeria”. The result was a unique portrait of this Afro-Brazilian religion, presenting the manifestations of nine orixás – spirits of nature. Masquerade takes on an ecological form with nature being woven into costume, recycling the environment. Ogum, deity of the hunt makes an appearance, and the altar of the trickster deity Exu – god of chaos, patron of boundaries and the travellers that cross them. Charged with colour and a deep sense of drama, Galembo’s portraits unite the human and the divine, the tangible and intangible, immortalising encounters with the supernatural and mythological through her portraits.

“I don’t have any directory. It’s always full of surprises. I work with whatever appears”, she says of her working process. We’re a world away from functional dressing. Masquerade elevates the act of dressing into a work of wearable art, intricately weaving meaning into design, and eventually, when worn – metamorphosing mere mortals into divine creatures. “I’m not a very fashionable kind of person”, she says. “But as a photographer, I have always been interested in ritual and acts of transformation”.

Though masking is increasingly rarefied in Africa today, Galembo’s work tributes the surprising persistence of this art form. Traced back to past Paleolithic times, the mask in Africa has long been a sacred art form, one whose power comes alive through the chosen and initiated, performed through ritual, dance – and possession. Beyond a celebration of cultural heritage, it is believed that the spirits of the wearer’s ancestors join in the ceremony, making their earthly presence known through possession, infusing the divinity into flesh. Often, it is necessary to ask the spirit’s permission to be photographed, reports Galembo. Through ceremonies, initiations, blessings and rituals, the mythology of the ancestors lives on. The masquerade’s ends are manifold – from crop harvesting, fertility, peace, war, and even political satires. “There are political masquerades’, says Galembo, “sometimes they’ll have spoof on a politician during the elections. Or sometimes the rituals associated with the masquerade will act out stories involving political figures”. But essentially, Galembo emphasises her work as “non-political. It’s more about the spiritual – it’s a celebration of life”, she says.

Poetic, theatrical, and mysterious, Galembo’s work provides an invaluable contribution to ethnographic study. Once an integral part of African life, the tradition and culture around masking has progressively dissipated as a result of the loss of tribal culture and identity, one of the many consequences of parcelled out territories to Colonial governments and displacement of peoples by colonialism. Against the pressures of contemporary society, modern religion and a rapidly increasing urban migration, masking nevertheless survives, sometimes as an alternative social practice; finding modern expressions in events such as Haiti’s annual Jacmel Carnaval [Jacmel Kanaval – Haiti’s Pre-Lenten festival], which Galembo attends every year since 1994. Feeling a particular affinity to Haiti, Galembo has herself participated in the annual Sodo pilgrimage, as well as taking part in their water rituals and ceremonies. “I’m interested in that energy, the music, and the dance”, she says, “most of the photographs that I show do not necessarily reveal those aspects – I’m more interested in creating the portraits and really documenting the ritual clothing”.

As the 21st century moves along, so do the aesthetics of spirituality. Galembo’s work documents their move into modernity – for better or for worse. “Things are in a constant state of transformation”, Galembo comments, “hopefully these traditions will carry on – who’s to know. But I don’t go somewhere expecting it to look how it used to”. If recycling Christmas ornaments into African ritual wear might seem a curious choice at first, Christian artefacts and symbols have sometimes been integrated into African diasporic religions – such as Vodoun, with Haitian Vodoun initiates notably adopting figures of the Virgin Mary into altars dedicated to the Goddess of Love Erzulie. Galembo’s portraits tell the story of the richness of spiritual heritage, and the rare artistry of these creations imbued with spiritual, cultural, political, and sometimes magical intentions. The alien figures speak of masquerade as an act of imagination, beauty, and fantasy. It’s a vision of reconciling art into life, and, saluting its ancient origins – to manifest and reaffirm the myths of the ages.

A selection of works by Phyllis Galembo is now on view at The Three Squares Studio in New York. The exhibition is titled Maske – A Collection of Photographs by Phyllis Galembo, on view through December 22 2012, New York, USA.